Uplifting, uniting and empowering the Black community at UNC Charlotte: The origins and legacy of the Black Student Union

February 8, 1969, marked the first anniversary of the Orangeburg Massacre, where South Carolina Highway Patrol officers shot and killed three Black protesters and injured 28 others.

Just one day before, on Feb. 7, civil rights activist Reginald A. Hawkins and UNC-C Students for ACTION (Active Committee for Truth, Individualism, Opportunity, Now) held a vigil on campus in honor of the fallen protesters.

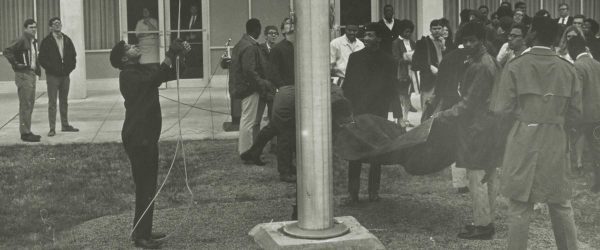

At the vigil, the students, led by Benjamin Chavis Jr. and Ronald Caldwell, replaced the American flag with a solid black flag. In his oral history interview, Chavis recounts that during the Vietnam War, “people had a very passionate connection with the United States flag” and that they were “trying to make a statement for African Americans and for Black people to be taken more seriously by the university.”

The flag, which was to be flown at half-mast Feb. 7-9, was taken down that afternoon by the University, prompting the Black Caucus UNC-C to write to University administration and request its immediate replacement. Their request was denied, but the result was the formation of the Black Student Union (BSU).

In a statement released on Feb. 24, 1969, the newly formed Black Student Union wrote the following:

“We the Black students at U.N.C.-C. have deem it necessary to form a Black Student Union to voice, express and relate the will of Black people on campus and in the Black community as well. We deem this necessary because we as Black students intend to combat the institutionalized racist educational system at U.N.C.-C. which affects Black people on campus and in the Black community. Therefore, we demand that the university and the student legislature immediately recognize the Black Student Union as an official campus organization.

We intend to confront the university and the student legislature on Monday, Feb. 24, 1969, at 11:30 with our demand. If our demand is not immediately met other actions will be taken.”

The Student Government Association refused to accelerate the process that would have allowed the Black Student Union to be chartered by the University.

On Feb. 26, Chavis, Caldwell and T.J. Reddy led members of the unchartered Black Student Union to the administration building along with a list of 10 demands, all aimed at increasing UNC Charlotte’s academic inclusivity.

Though Chancellor Dean Colvard was in the hospital in Chapel Hill and the vice chancellor for academic affairs, William McEniry, was unavailable, Bonnie Cone, UNC Charlotte’s founder and the vice chancellor for Student Affairs, invited Chavis, Caldwell and Reddy into her office.

Their conversation was tense; the students’ conviction was at odds with Cone’s wariness about how they were making their demands. Nevertheless, Reddy recalls Cone telling them “I’m here to listen and to help you be more represented here.”

![[Picture of 10 Demands with notes from Bonnie Cone]](https://inside.charlottewp.psapp.dev/wp-content/uploads/sites/1289/2024/05/bsu-10-demands-with-comments.jpg) Another meeting — this time unpublicized and private — took place on Feb. 28 and included Cone, McEniry, Chavis and four other unnamed representatives of the Black Student Union. Later statements released by both groups described their discussion of the demands as open, productive and civil.

Another meeting — this time unpublicized and private — took place on Feb. 28 and included Cone, McEniry, Chavis and four other unnamed representatives of the Black Student Union. Later statements released by both groups described their discussion of the demands as open, productive and civil.

Yet on the morning of March 3, when about 20 Black Student Union members requested that the administration provide written responses to the 10 Demands, McEniry refused, saying that he did not have the authority to make anything official. He then learned that the story had been leaked to a reporter and reportedly blamed the student representatives, who adamantly denied they were the source. By this point, each party believed the other had gone back on its word.

In response, the 20 BSU members, who were present as a show of support, began to protest, with Chavis reading the demands and others trying again to raise a black flag. Worried that the Black students might try to occupy the administration building, McEniry and other University staff called the police to disperse the growing crowd.

Despite the nonviolence, the day ended with Black students being arrested and receiving no public support for their demands.

Despite the nonviolence, the day ended with Black students being arrested and receiving no public support for their demands.

On March 20, Chancellor Colvard responded to the demands. The efforts of UNC Charlotte’s Black students set in motion University-wide changes and advancements, including what would become the Department of Africana Studies.

It was not until Nov. 26, 1969, after months of relentless work, that the members of the Black Student Union were able to establish the group as an official student organization.

Today, more than 50 years later, the Black Student Union is “rooted in holding true to the values and goals of the founders,” said BSU publicist Maliah Graves. “Much of what we do still revolves around the same core legacy.”

The BSU’s dedication to Black UNC Charlotte students has continued during COVID-19, though they now rely on social media to connect with them. “We want to spread awareness and keep engagement in the safest way possible.”

The BSU’s dedication to Black UNC Charlotte students has continued during COVID-19, though they now rely on social media to connect with them. “We want to spread awareness and keep engagement in the safest way possible.”

Graves continued, “the Black Student Union still has the mission of uplifting, uniting and empowering the Black community at UNC Charlotte. We want BSU to feel like a family, where students can really be heard, seen and advocated for.”

Sources for this piece include the Special Collections/University Archives in Atkins Library, The Carolina Journal, and the UNC Charlotte Black Student Union.