Researcher probes planet’s history through genes of shy creatures

They are in your basement, or in your yard, hiding in the fallen leaves at the foot of your trees. They are living relics, walking the earth virtually unchanged since they first appeared 400 million years ago– about twice as long ago as the first dinosaurs. They are hiding in plain sight, but in their genes they hold a record of the deep history of the planet and its landmasses.

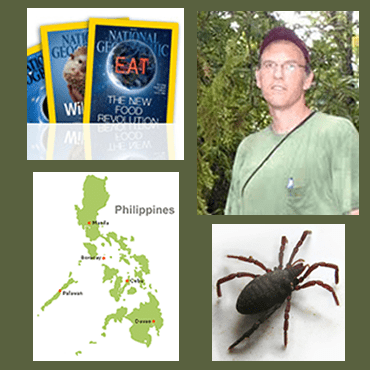

And they are also the reason National Geographic is helping send UNC Charlotte bioinformatics postdoctoral researcher Ronald Clouse to the Philippines this summer, and asking him to blog about the experience.

These unusual animals are Opiliones, otherwise known as daddy-long-legs or harvestmen.

Though most of us confuse them with spiders (there are some varieties of spider that are called “daddy-long-legs”) they are actually a significantly different group of arachnids more closely related to scorpions, from which they diverged a little over 400 million years ago, shortly after scorpion ancestors first came on land. Contrary to their popular name, not all daddy-long-legs have long legs – those Clouse will be studying (Cyphophthalmi or “mite harvestmen”) look like tiny short-legged spiders and live in humid leaf litter, where they tear up and eat plant matter and even tinier insects with the miniscule claws they have in place of spider fangs.

They are obscure animals, and though widespread and probably present nearly everywhere on the planet, there is a lot we don’t know about them. Some of the things that we do know about them, however, make them important to science, Clouse pointed out.

“We think they are exciting animals, we think they give us a lot of great information about deep, deep history,” he said.

First of all, they have passed through a very long stretch of time virtually unchanged. “Daddy-long-legs evolved from scorpions – they are sister groups – and scorpions started to come out on land about 425 million years ago and at 400 million years ago there is a beautiful fossil from Scotland of a daddy-long-legs that looks almost exactly like the ones in your basement today,” he said.

Clouse noted that Opiliones seem to have quickly found land niches everywhere and then remained happily in them.

“We have a fossil of the southeast Asian ones from 100 million years ago in amber,” he said. “It looks like they first showed up from 425 to 400 million years ago and they quickly evolved into these really elaborate morphologies that we have today. And it was another 200 million years before the dinosaurs showed up, and the dinosaurs blink out after a little more than a hundred million years. These guys have been hanging tough the whole time.”

Second of all, it turns out that daddy-long-legs have perfected a lifestyle that makes them extreme homebodies.

“The reason we like this group of animals is they don’t go anywhere in their lives and when we find them in the forest floor in the leaf litter, even if we find a bunch of them, there will be a completely different species a few kilometers over. They are very highly local,” he said.

Clouse knows that Opiliones are confirmed stay-at-home types thanks to bioinformatics.

“When we sequence their DNA we find that all the ones in this forest, even though some groups may be spread out over wider areas, when you look at it population by population, there is almost no gene flow,” he noted. “Everyone here has one set of sequences, everyone there has a completely different set of sequences.”

And the small, leaf litter dwelling types turn out to be even more localized.

“For these little guys – we were down in Florida sequencing, and we found that just a few meters away the sequences were different. When we find them in the forest floor in the leaf litter, even if we find a bunch of them, there will be a completely different species a few kilometers over. They are very highly local. And the entire group, which is found around the world, exhibits the same high-need microniche requirements and the same behavior.”

This old, established pattern of localization has some important implications that go far beyond invertebrate biology. You can find markers for the ancient history of the earth in a daddy-long-legs’ genes, Clouse explained.

“The end result of this is that their current distribution around the world is due to the movement of continental landmasses. So, when we reconstruct their history from their DNA, we get a nice match to the history of the landmasses on which they live,” he said.

For those interested in following Clouse’s blog from the field later this summer, visit his National Geographic news watch author Web page.